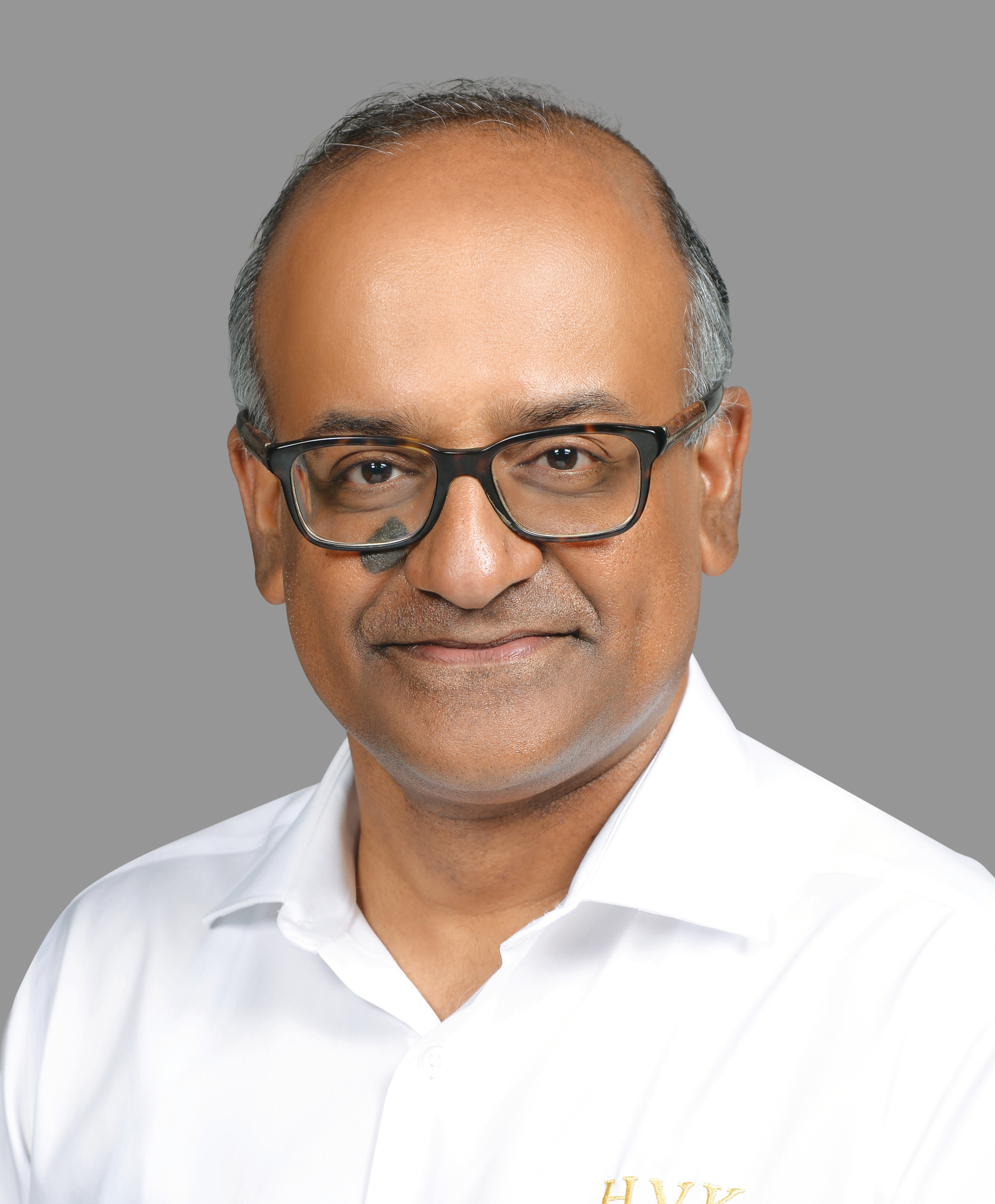

WORDS BYV.Sriram

PHOTOGRAPHY BYRamya Reddy

Madras University Annexure

Chennai: Voices from a City gathers three pieces by Sriram V, chronicler of Madras and its layered histories. Moving between architecture, music, and neighbourhood life, his writing reveals how the city continues to listen to itself — in brick and lime, in song and cinema, in its crowded streets and quiet corners. These reflections, drawn from his larger body of work, remind us that heritage is not static but lived: spoken, sung, and walked through every day.

Senate House; Indo-Saracenic style of architecture credited to RF Chisholm

Listening to Heritage

If you were to wander around the older parts of the city, the chances are that you will come across several massive, red-coloured buildings. The colour is not painted but that of exposed brick, and it was a style that was prevalent for much of the 19th century in Madras.Many deem these to be a celebration of colonial heritage, but in reality, they are celebrations of collaborative heritage – of at least one aspect of the city when ruler and the ruled worked together.

Madras, as we know, was the birthplace of the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture. The birth may have been in the 18th century, but it needed a full 100 years for it to suddenly burst forth in profusion. Much of the credit for that goes to the architect RF Chisholm. His first commission here was the design for the Presidency College in the 1860s. He does not seem to have thought of the Indo-Saracenic style in the initial days, but by the late 1860s, he, having seen various monuments scattered across South India, came to be a firm believer. And he achieved much of it in collaboration with native artisans. Thus, the plan was all Chisholm’s, but when it came to execution, especially by way of embellishment in woodwork, tiles, painting, glass, and friezes, he largely left everything to the Indian artisans.

Chisholm's work in Madras ended in the 1880s, but he had ensured that Indo-Saracenic was the preferred architectural form for the empire, and it was carried from here all across the country. However, post-independence, this form went into decline because it was seen as a colonial architectural form. Forgotten was the fact that thousands of Indian artisans had worked on creating these masterpieces. Many such structures, deprived of even basic maintenance, suffered and came to be demolished. The period between 1980 and 2000 was perhaps the worst. Several great architectural marvels were lost. Gradually, a new awareness came about.

With active campaigning by the Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage and the writings of renowned voices, such as S. Muthiah, the indefatigable chronicler of the city, people came to see the red buildings in a new light. The turning point was perhaps when Chepauk Palace, the mother of all Indo-Saracenic buildings, caught fire, and a minister promptly declared that what was left would be demolished and the space dedicated to a marriage hall. The public outcry was unprecedented, and that forced the government to change its views. Restoration began and continued for more than a decade after the fire—an indication of how difficult it is to restore what is easily destroyed. Since that transformative moment, there has been a resurgence in the restoration of Indo-Saracenic buildings, and many of them are now coming back into the limelight.

To me, it is a celebration of the city when it accepts its past, learns to respect what has gone into the creation of these buildings, and creatively repurposes them for modern use. This is enlightened vision at its best.

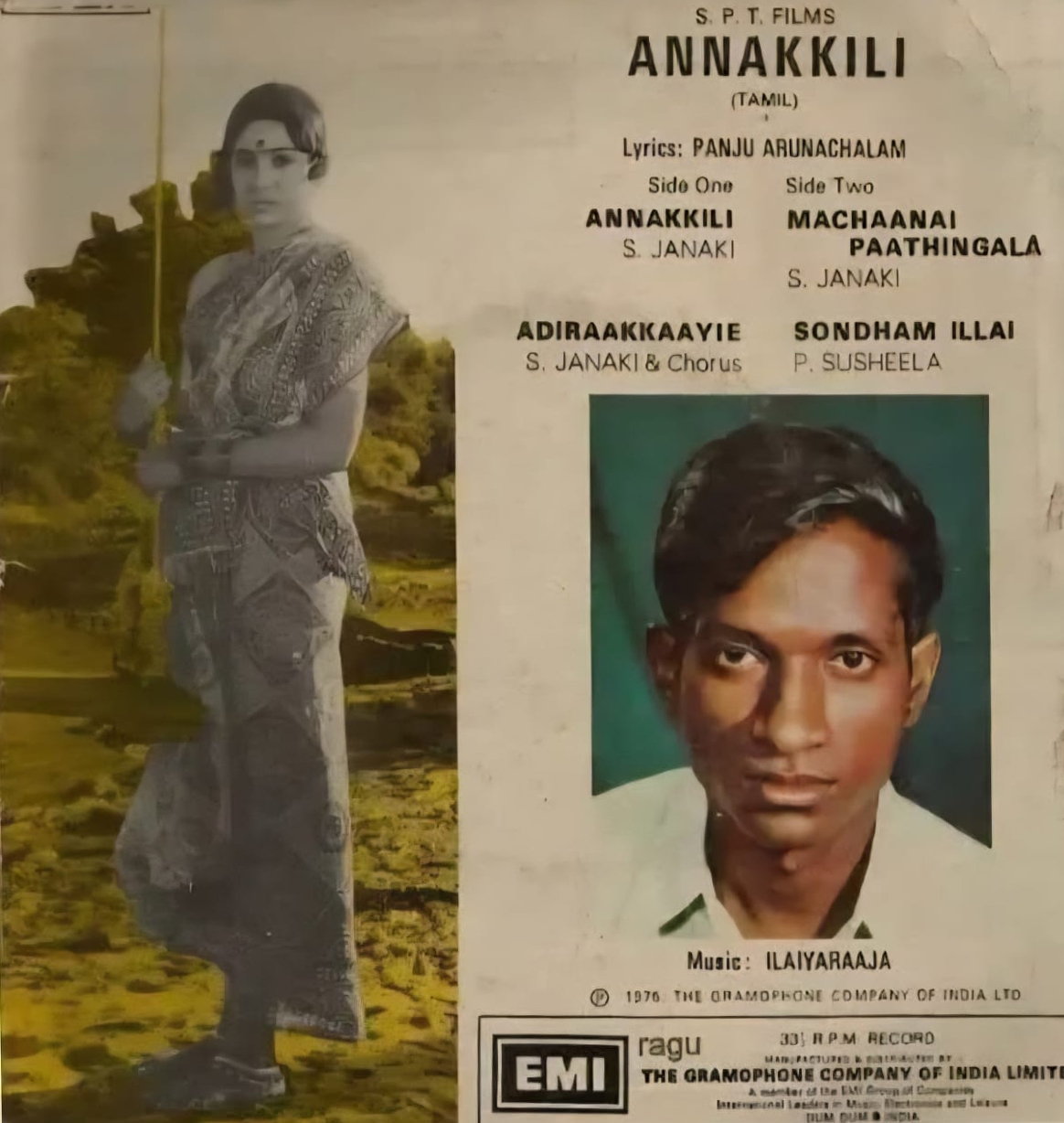

An LP cover of the first film of Ilayaraja

Screen Shots

A few years ago, Chennai received the Creative City tag from UNESCO. It was in recognition of the city’s contribution to music, and after all, there is a lot that can be said about music and Chennai. The city, home to the unique December music festival, is also a place where Western classical music, jazz, rock, pop and several other forms from across the seas flourish. It is home to Musée Musicals, a music emporium that has been in operation for more than 180 years. Apart from selling musical instruments, the museum offers classes in Western classical music and conducts examinations on behalf of Trinity College, London. Chennai is also home to film music, and perhaps that is one of the largest single corpuses, if you look at the contributions of lyricists, music directors, singers and orchestral ensembles from 1931 onwards.Our home was a microcosm of all this. On the paternal side, my grandmother was passionate about Carnatic music and ensured that all her children and grandchildren were taught the art from the age of six onwards. Grandfather, after having retired from the railways in a very senior position, took to Sanskrit and composed a few songs as well. Aunts, uncles, dad, cousins—everyone sang, and therefore it was no wonder that I took to music from a very early age. Late at night, my dad would tune in to AIR’s western classical music hour, and I loved it.

My mother’s brother was known for his collection of recordings of Carnatic music masters, and I greedily absorbed those as well. Late at night, my dad would tune in to AIR’s western classical music hour, and I loved it. It was, however, paternal uncle, namely father’s younger brother, who brought film music to the household. He was perhaps the most musical of all of us. A great voice taught by some of the great masters of Carnatic music meant he could reproduce any tune effortlessly. Much to grandmother’s joy, he would sing Carnatic music, and then, to her distress, he would turn to the radio and play Hindi and Tamil film music.

We would all listen to the great hits from the 1960s till the mid-1970s; then our joint family broke up, and we went in various directions. My uncle went to America, and therefore, his awareness of Indian film music stopped in the 1970s. Years later, when I would visit him, he would still regale me with Tamil and Hindi hits from "his era," as he referred to it. This was despite his being terminally ill by that time.

In this way, I came to love Hindi and Tamil film music, and later, growing up in Calcutta, I also developed a fondness for Bengali film music, apart from Rabindra Sangeet and several other minor variants. Today, I consider myself fortunate that I can appreciate various musical forms thanks to the familial influences. There is just one disadvantage: I am not the kind of person who can work on anything else while listening to music, and therefore, it demands that I have free time to devote to it!

Fort St.George

Black Town, White Town!

They remain my favourite destinations in the city.George Town, formerly Black Town, is easily the most fascinating. It is a warren of streets, crumbling houses, reflective of a way of life long gone, centuries-old business establishments, educational institutions, places of worship, community hospitals, and markets. There is now of course a huge chunk of ugly modern construction which has ruthlessly replaced what has vanished without a trace. Traffic today may be a nightmare in George Town, and conservancy services are at a bare minimum, but the place is full of life. If you can brave the congestion and look up, you may be rewarded or horrified beyond belief, depending on what has caught your eye. You may be rewarded for noticing an exquisite gable hanging on for dear life in the onslaught of new construction, bad weather, zero maintenance, and pollution. Rewarded by a singular stained-glass panel, whose very existence makes one wonder how it survived. And then, horrified by the jungle of electric wires that stretches from building to building with no insulation or protection of any kind, it does make you wonder how the whole of George Town has not gone up in one vast plume of smoke.

I first learned about the charms of George Town from my maternal grandfather. He delighted in walking around there, taking in the aroma of eateries, the specialized trades of certain streets, the tower of Babel, when it came to language, because this was where you could hear Tamil, Telugu, Gujarati, Marwadi, Urdu, etc and then probably if you listened closely enough, several dialects born of these languages.

I first learned about the charms of George Town from my maternal grandfather. He delighted in walking around there, taking in the aroma of eateries, the specialized trades of certain streets, the tower of Babel, when it came to language, because this was where you could hear Tamil, Telugu, Gujarati, Marwadi, Urdu, etc and then probably if you listened closely enough, several dialects born of these languages.

Thatha loved his town, and so does my mother, who has only recently given up the temptation of going on a walkabout there. George Town may be an urban nightmare, but to me, it truly represents the way Chennai comes together — people living and thriving as one in an atmosphere of camaraderie.

In sharp contrast, and perhaps entirely in keeping with that side of the family, White Town or Fort Saint George was introduced to me by my culturally refined father. Not for him and his siblings, or for that matter, his parents, the hurly-burly of George Town.

In sharp contrast, and perhaps entirely in keeping with that side of the family, White Town or Fort Saint George was introduced to me by my culturally refined father. Not for him and his siblings, or for that matter, his parents, the hurly-burly of George Town.

It was a family that believed in cloistered learning. And so it was my dad who, when I was six, first took me to Fort Saint George -the home of the colonial masters. This part of Chennai speaks to you in different ways — the story of ambition, greed, commerce, and how these forces have shaped history. Fort Saint George may have given birth to George Town, but today, White Town is just an administrative headquarters with numerous shell-like buildings in varying stages of maintenance, care, or even crumbling. It comes alive only during the day when bureaucrats, ministers, and army officers go about this space. During the late evenings to early mornings, this part of Chennai is just a tableau of brooding army buildings, the Church of Saint Mary, and the museum, which was once the Exchange Building. This too has its history, but it doesn't reveal itself easily, and only upon probing does one realise that the history of White Town and George Town is really the history of Madras, and what this beautiful city is all about.

Vignette of a plaque, St. Mary's Church